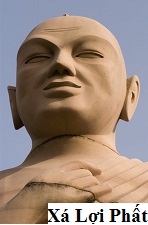

Shariputra was a Dharma Nature elder. At the age of eight he studied and mastered all the Buddhadharma in only seven days, and he could out-debate all the Indian philosophers. His name is Sanskrit. His father’s name was Tisya and his mother’s name was Sarika. Hence he was known as Upatisya, “Little Tisya,” and as Shariputra, the Son (putra) of Sari.

The word Shariputra may be translated three ways,

- “Body son” because his mother’s body was extremely beautiful, and her features very refined;

- “Egret son” due to his mother’s eyes which were as beautiful as an egret’s and,

- “Jewel son” because her eyes shone like jewels. Shariputra’s mother’s eyes were beautiful, and when she bore this jewel-eyed son, his eyes were beautiful, too.

He was the foremost of the Sravakas in wisdom. While still in the womb, he helped his mother debate, and she always won. In the past, whenever she had debated with her brother, she had always lost; but while she was pregnant with Shariputra, her brother always lost.

“This isn’t your own power,” he said. “The child in your womb must be incredibly intelligent. He is helping you debate and that’s why I lost.” Thereupon he decided to study logic and travelled to Southern India where he studied for many years.

There was no electricity at that time yet, but he studied by day and by night. He mastered the Four Vedas, the classics of Indian knowledge, without wasting a moment. He didn’t take time to mend his tattered clothing, wash his face, or even cut his nails which grew so long that everyone called him “The Long-Nailed Brahmin.”

Having mastered various philosophical theories, he returned to debate with his sister’s son. He had spent a great deal of time preparing for the event, and felt that if he lost it would be the height of disgrace. “Where is your son?” he asked his sister.

“Shariputra has left the home-life under the Buddha,” she said.

The Long-Nailed Brahmin was displeased. “How could he?’ he said. “What virtue does the Buddha have? He’s just a Sramana. Why should anyone follow him? I’m going to go bring my nephew back.”

He went to the Buddha and demanded his nephew, but the Buddha said, “Why do you want him back? You can’t just casually walk off with him. Establish your principles and I’ll consider your request.”

“I take non-accepting as my doctrine,” said the uncle.

“Really?” said the Buddha. “Do you accept your view of non-accepting? Do you accept your doctrine or not?”

Now the uncle had just said that he didn’t accept anything. But when the Buddha asked him whether or not he accepted his own view of non-accepting, he could hardly admit he accepted it for that would invalidated his doctrine of non-acceptance. But if he said that he didn’t accept it, he would contradict his own statement of his doctrine and his view. He was therefore unable to answer either way.

Before the debate, he had made an agreement with the Buddha that if he won he would take his nephew, but if he lost, he said that he would cut off his head and give it to the Buddha.

The uncle had bet his head and lost. So what did he do? He ran!

About four miles down the road he stopped and thought, “I can’t run away. I told the Buddha that if I lost he could have my head. I’m a man, after all, and I should keep my word. It’s unmanly to run away.” Then he returned to Shakyamuni Buddha and said, “Give me a knife, I’m going to cut off my head!”

“What for?” said the Buddha.

“I lost, didn’t I? I owe you my head, don’t I?” he said.

“There’s no such principle in my Dharma,” said the Buddha. “Had you won, you could have taken your nephew, but since you lost, why don’t you leave home instead?”

“Will you accept me?” he said.

“Yes,” replied the Buddha.

So not only did the nephew not return, but the uncle didn’t return home either.

At age eight, the Great, Wise Shariputra had penetrated the Real Mark of all dharmas in only seven days, and defeated all the philosophers in India. When Shakyamuni Buddha spoke the Amitabha Sutra without request, Shariputra was at the head of the assembly, because only wisdom such as his could comprehend the deep, wonderful doctrine of the Pure Land Dharma Door.

Not only was he foremost in wisdom, he was not second in spiritual penetrations either. Once a layman invited the Buddha to receive offerings. Shariputra had entered samadhi, and no matter how they called to him, he wouldn’t come out. He wasn’t being obnoxious by showing off, thinking, “I hear them, but I’m not moving, that’s all there is to it.” No, he had really entered samadhi.

When he didn’t respond to the bell, Maudgalyayana, foremost in spiritual powers, applied every bit of strength he had, but couldn’t move him. He couldn’t even ruffle the corner of his robe. This proves that Shariputra was not only number one in wisdom, but also in spiritual penetrations. He wasn’t like us. If someone bumps us while we sit in meditation, we know it. Shariputra had real samadhi.

We should look into this: Why was Shariputra foremost in wisdom? Why was he called “The Greatly Wise Shariputra?” It’s a matter of cause and effect. In a former life, in the causal ground, when he first decided to study, he met a teacher who asked him, “Would you like to be intelligent?”

“Yes I would,” said Shariputra.

“Then study the dharma-door of Prajna wisdom. Recite the Great Compassion Mantra, the Shurangama Mantra, the Ten Small Mantras, and the Heart Sutra. Recite them every day and your wisdom will unfold.”

Shariputra followed his teacher’s instructions and recited day and night, while standing, sitting, walking, and reclining. He didn’t recite for just one day, but made a vow to recite continuously, to bow to his teacher, and to study the Buddhadharma life after life. Life after life, he studied Prajna, and life after life his wisdom increased until, when Shakyamuni Buddha appeared in the world, Shariputra was able to penetrate the Real Mark of all dharmas in only seven days.

Who was his former teacher? Just Shakyamuni Buddha! When Shakyamuni Buddha realized Buddhahood, Shariputra became an Arhat, and because he obeyed his teacher, he had great wisdom. He never forgot the doctrines his teacher taught him, and so, in seven days, he mastered all the Buddha’s dharmas.

When one has not studied very much Buddhadharma in the past, one learns mantras and sutras slowly. One may recite the Shurangama mantra for months and still be unable to recite it from memory. It is most important, however, not to be lazy. Be vigorous and diligent. Like Shariputra, don’t relax day or night. Those who can’t remember should study hard, and those who can should increase their efforts and enlarge their wisdom.

You should consider, “Why is my wisdom so much less than everyone else’s? Why is his wisdom so lofty and mine so unclear? Why do I understand so little? It’s because I haven’t studied the Buddhadharma.” Now that we have met the Dharma we should vow to study it. Then in the future we can run right past Shariputra and study with the Greatly Wise Bodhisattva Manjushri, who is far, far wiser than the Arhat Shariputra. This is the cause behind Shariputra’s wisdom, a useful bit of information.